by TogetherforEurope | Aug 22, 2018 | 2016 Munich, Experiences, reflections and interviews, News

It´s a matter of growing ever more into a “culture of trust”, including a worldly trust in God.

Herbert Lauenroth’s presentation at the International Congress of “Together for Europe – Munich 2016″ is as current as ever. Here is the full text.

Dear friends,

I would like to start my – rather fundamental – reflections on the subject of fear, fear in Europe, with two striking biblical respectively secular images:

1 In a dramatic moment in the book of Genesis God calls man: “Where are you, Adam?” This call is addressed to the one who has sought refuge in the underbrush, full of shame and driven by fear. To the one hiding from the sight of God because he has become aware of his existential nakedness and wretchedness. This image depicts the present situation in Europe in a quite drastic way: A continent barricading and entrenching itself in its seemingly hopeless presence. Europe is hiding in the underbrush, stuck in the entanglements of its own limitations and a history of guilt. This underbrush is Idomeni, the Macedonian border, the barbed-wire fence at the Hungarian-Serbian border, but also the various exclusions in society.

If we read the biblical scenario as for turning Europe into a fortress, a measure against migrants, it allows another different reading: It´s the European sovereign standing before us, it´s his exposure and homelessness we`re looking at. He is the real refugee, trying to escape from himself, the most fatal of all flights. Therefore Europe has to hear this call from the Biblical God once again. It´s a question of its destiny, mission and responsibility for itself and the world: “Adam/Europe, where are you?”

2 This image of an existential narrowness God calls out of, finds its counterpart in the visions of men`s cosmic forsakenness in an indifferent, inhospitable universe. Philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal expressed it like this: “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me!” It´s about a sense of being appalled or exposed that frightens man, as he is isolated and being thrown back on his own. In European history this recurring theme has been described as “loss of the center” or “transcendental homelessness”.

3 However, this fear of loss of self and the world can make room for new experiences at the same time: Czech poet and President Vaclav Havel, looking back on the peaceful revolutions in Eastern Central Europe in 1989/90, spoke of fear as “fear of freedom”: “We were like prisoners who had become accustomed to the prison, and then, being released to the long-desired freedom out of the blue, did not know how to deal with it and became desperate because they constantly had to decide on their own and take responsibility for their own life.” It is, according to Havel, to face this fear. This is how it “enables us to acquire new abilities: The fear of freedom can be exactly what teaches us to fulfil our freedom. And fear of the future can be exactly what forces us to do everything to make the future better.”

Finally, the great protestant theologian Paul Tillich takes fear for the basic experience of human existence: “The courage to be,” he writes, “is rooted in the God who appears when God has disappeared in the fear of doubt.” This means: only the experience of fear – as the loss of an image of God, man and the world that was formerly formative and considered to be immutable – unleashes what is called the “courage to be“. The true – divine – God appears so to speak in the heart of fear, and he alone causes de-frightening. In turn this experience leads man to deeper experiences and horizons of being. God reveals himself in the supposed facelessness and ahistoricity of the world as the face of the other.

4 It is therefore necessary to descend into these ‘inner rooms of the world’ of biographical as well as collective fears and experiences of loss, in order to meet the God who saves us. Two examples:

4.1 Yad Vashem: my visit to the Shoah memorial site last autumn is an unforgettable experience for me: I walk through the mazy-like architecture as if in a daze and finally reach the Children`s memorial, a subterranean space where the light of burning candles is reflected by mirrors. It`s a dark resonance space of bodiless voices, which unceasingly recall the elementary life-data of the innocent victims and I feel a new, deep solidarity – especially in view of this profound primal fear of not only being physically destroyed, but being even eliminated from the cultural memory. The testimony of this place becomes my own experience: to provide a place for the lost name, to preserve a memory for the name of God and its creatures. My guestbook entry is a sentence of the prophet Isaiah that expresses both my consternation and the new hope in the captive closeness of a fatherly God: “Fear not, for I have redeemed you. I called you by name, you are mine!” (Isaiah 43,1)

4.2 In view of the great European tales of fear, Czech philosopher and theologian Tomáš Halík describes a similar experience: “We do not build the bold project of European unity on unknown ground or wasteland. We build it on a ground, in whose layers forgotten treasures and burned debris are stored, where gods, heroes and criminals are buried, rusted thoughts and unexploded bombs. From time to time we have to set out on looking into the depths of Europe, into the underworld, like Orpheus to Eurydice, or the dead Christ to Abraham and the fathers of the Old Testament.”

5 For me, these various “descents into the depths of fear” converge in the description of the baptism of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew: “As soon as Jesus was baptized, he went up out of the water. At that moment, heaven was opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and lighting on him. And a voice from heaven, said, ‘This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased.’“ (Matthew 3:16–17)

We have to descend with Christ to reach that point of origin, above which the sky opens up quite surprisingly. It´s where God’s law of life shows itself: “What comes from above must grow from below.” In this way, in, with and through Jesus, the “fraternal” community of solidarity is formed, in which the individual members do not only recognize themselves as “sisters and brothers” but also as “sons and daughters of God”, in which “dignity of man” and “God-likeness” form an indivisible unity.

6 In his book “Letters and Papers from Prison” (Widerstand und Ergebung) Dietrich Bonhoeffer describes the core of the Christian identity as a response to the question of Jesus at the moment of his mortal fear in Gethsemane: “Could you not watch with me one hour?” (Matthew 26,40) – It is an invitation to the night watch at the side of Jesus, in his presence facing the Father, in a secular – supposedly godless – world. This presence of Jesus transforms different locations into places of experience and expectation of Trinitarian life.

7 In this key section of the Gospel of Matthew “fear” appears as a privileged place of learning for our faith where diffuse, “blind” fears converge and transform into the authentic “fear of God” of Jesus that offers new insights.

As:

- In, with, and through Jesus, de-frightening takes place as a real frightening-through of man towards God: The supposed exposure of the Son changes to devotion to the Father.

- Unity grows as an experience of mutual trust. It grows from sensitivity for the mystery of God which is not at our disposal, the otherness (alterity) of the other. French-Jewish philosopher Simone Weil expresses this experience in a striking way: It´s only the unconditional “consent to the distance of the other” that allows for authentic closeness and communion with God and man.

- So that´s what it is about: Preferring the unknown, the unfamiliar, the marginalized – as a “learning place” of faith – in, with, and through Jesus.

- This especially applies to the different charisms and their communion: in Paris in November 2013 at a meeting of Together for Europe with Jean Vanier, founder of “L’Arche”, it became apparent to us: one of the real aims of the charisms is also to receive the “charism of the world” and to reflect it to this world. Vanier’s testimony has been very impressive: primarly it´s not about living with and for the “addressees” of the Beatitudes of Jesus, but from In fact they – the supposedly needy and receiving ones – are the God-gifted and giving ones. They are the bearers of a message, a presence of God that has to return to the center of our societies from their margins. Klaus Hemmerle, Bishop of Aachen and religious philosopher wrote concisely: “Let me learn from you the message that I have to pass to you”.

8 This attitude, however, requires a “thrust reversal”, a true metánoia of many a Christian on their understanding of themselves and the world. It calls for a new faith in God’s love for the world which is revealed in Christ. It´s a matter of growing ever more into a “culture of trust”, including a worldly trust in God that is founded in Jesus.

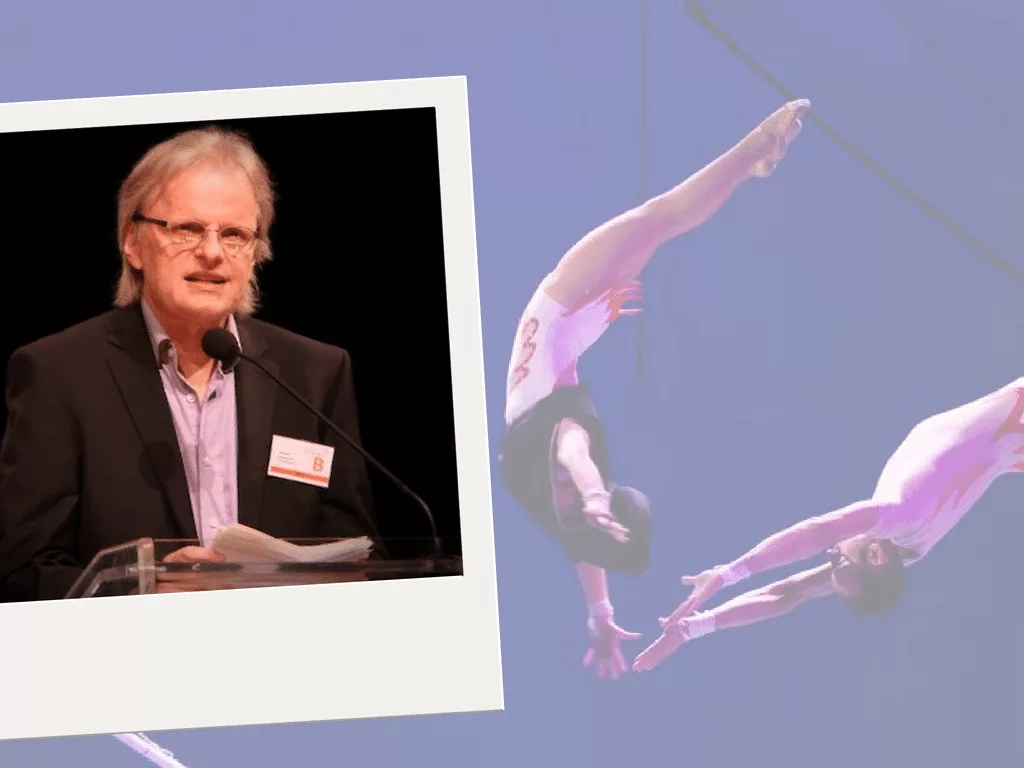

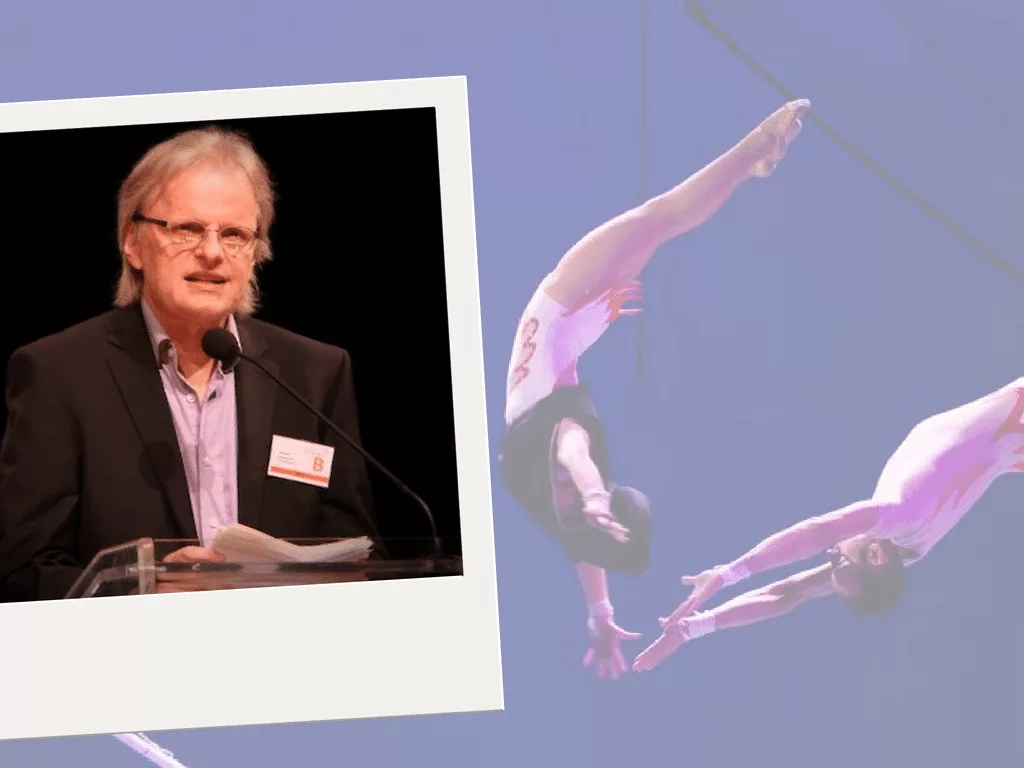

9 Looking up into the dome of the Circus-Krone building, we might think of some trapeze artists. For me, they are the true artists of de-frightening: Flyers hovering in the air, always taking the risk of trust, letting go and stretching out again for future spaces. An artistic moment in that prophetic and always fragile, risky intermediate state of “grace and gravity”: The grace of weightlessness, yet the creature always having a knowledge of being held and secure, in a certain sense “redeemed” from itself and liberated for turning towards the other.

With this in mind, Henri Nouwen writes: “A flyer must fly, and a catcher must catch, and the flyer must trust, with outstretched arms and open hands that his catcher will be there for him. […] Remember that you are the beloved child of God. He will be there when you make your long jump. Don’t try to grab him; he will grab you. Just stretch out your arms and hands – and trust, trust, trust! “

Herbert Lauenroth, Ecumenical Center Ottmaring (Germany), in Munich, Circus-Krone-Bau, 01/07/2016

Photo: trapeze artists ©Thierry Bissat (MfG); H. Lauenroth: ©Ursula Haaf

by TogetherforEurope | Apr 30, 2018 | 2018 Europe Day, Experiences, reflections and interviews, News

Is there a future for Europe? What do you think is the contribution that Churches and Ecclesial Movements can offer in this respect?

There is indeed a future for Europe. Communities and Churches do have a role to play individually as well as together and as part of civic life which has been growing stronger. In time it will generate its own new political leaders and until then it will continue reinforcing its civic commitment. The greatest damage to society comes from the apathy of millions who do not attempt to make a positive contribution. So these communities have a precise role. They develop and exercise certain aspects that are important for the functioning of society (for example order, freedom, obedience, responsibility, equality, hierarchy, respect, correction, individual and collective ownership, truth and so on).

9th May is Europe Day. What does this date mean to you?

The choice of date to celebrate is at once understandable, good and also necessary. The question is how to celebrate. We would like to see a big scientific interdisciplinary conference taking place as well as other forms of celebration that would appeal to society at large. Rather than an official celebration, we were thinking that perhaps an event like that of the European Capital of Culture might be interesting. We know from experience that official celebrations tend to be political and that the exploitation of such occasions for political purposes has the effect of distancing people from the event.

If you were President of the European Union with their responsibilities and decision-making powers, what would be your priorities aimed at increasing the unity of peoples in Europe?

I would avoid uniformity, and aim at pursuing, reinforcing and accelerating integration, based on a mutual recognition of identities and on solidarity. The United States is an example of such an approach, where only one language is spoken, and a looser integration bonds were replaced by centralization. We would be for increasing the extent of international projects such as Erasmus for researchers and third level staff and gradually opening up to involvement of secondary education teachers; making a six-month period of studies abroad obligatory for university students independent of their field of studies, as well as running continuous inter-institutional courses between bordering countries.

How do you see Europe in today’s international political context?

I think it is facing two main challenges: Firstly, unity: if Europe does not succeed in becoming more unanimous in personifying unity, it will lose its position on the international scene; and secondly, corruption: any type of abuse, even the slightest one, be it political, moral, or sexual, damages greatly the international community independently of whether it is carried out by an authority or an individual. This can only be prevented through a continuous examination of conscience or reflection performed together.

It appears as if young people were not interested in politics. Do you think it is true?

Young people love to be practical. Abstract things do not appeal to them. The key is to increase numbers and invest money in international study programmes, so that young Europeans can have a chance to get to know Europe and its young people. Europe should also strive to define its main objectives in more concrete terms so that the young people can believe in them and become enthusiastic about them.

What do you think about populist tendencies? Are there better ways of going ahead Together?

Populism is a consequence of the latest economic crises as well as of military conflicts (for example foreign interference’s). It is also caused by nationalism. The European Union does not deal with nationalism efficiently which puts populists at an advantage. Furthermore, European citizens do not tend to have a direct relationship with European politicians. They often know only their own national political representatives who are the ones ‘listened to by the crowds’ and therefore directly responsible for how information from Brussels is transmitted in individual member states. In any case we need to learn to advance together. In what way? In the context of what was discussed so far, the first step might be to act on a personal level and gradually assume a collective responsibility, acknowledging the effectiveness and the role of acting together.

Zsófia Bárány PhD and Szabolcs Somorjai PhD, Hungary, researches in the field of modern sociology and economy, and politics and history of the Church

by TogetherforEurope | Apr 4, 2018 | 2018 Europe Day, Experiences, reflections and interviews, News

DISCUSSION

|

|

DIALOGUE

|

|

|

|

| Convincing the other about one’s own point of view |

|

Exploring and learning together |

| Trying to get the other to agree to it |

|

Sharing ideas, experiences and feelings |

| Choosing the best option |

|

Integrating different view points |

| Justifying, defending one’s own motivations |

|

In-depth understanding of each party’s arguments |

| Disproving the other’s idea, defending one’s own position (values, interests) |

|

Welcoming and understanding the other |

| Individual leadership |

|

Shared leadership |

| Partial vision |

|

Overall vision, synergy of different ideas |

Hierarchical and competitive culture:

Dependence, competition, exclusion |

|

Culture of cooperation, partnership and inclusion |

| Victory / loss |

|

Win-win, all participants gain |

See Pal Toth in Nuova Umanità, XXXVII (2015/3) 219, p. 320

Illustration: Walter Kostner ©

by Sr. Nicole Grochowina | Apr 4, 2018 | 2018 Europe Day, Experiences, reflections and interviews, News

A short contribution, seen from an historical perspective, to Europe’s religious foundations and their difficulties

„Not only do books have a destiny but terms do too.” These are the opening words of the extensive History of the West (Geschichte des Westens) published in 2009 by historian Heinrich Winkler. And although Winkler is specifically unpacking the term “the West”, he simultaneously presents arguments which form a basis for reflecting on Europe. The fact that terms and their meanings change can either be comforting, threatening or even a sign of hope which is precisely what is currently happening in Europe. It is therefore worth taking a closer look at his ideas.

Winkler also makes fundamental and noteworthy observations about Europe. Firstly, he states that Europe is still most strongly characterised by its religious nature. This might come as a surprise in view of lay and secular developments but secularisation on this scale can only be understood as a reaction to powerful religious influences which were marked by differences according to divine and temporal order right from the start. This is the historical context in which Europe was born even if Europe’s religious history was consequently one of division.

Secondly, Europe has never gone forward in a linear way. Rather than being a story of uninterrupted success, Europe is a story of fractures, destruction, new beginnings and the perennial dream of a single community of shared values. This community first emerged through “transatlantic collaboration” as Winkler calls it for there can be no Declaration of Human and Civil Rights without the 1776 Declaration of Rights. The perspective is therefore broad.

Thirdly, Europe is also characterised by the “contradiction between the normative project and political practice” (Winkler, 21) which is why its revolutionary goal of freedom and equality was not achieved at the same time. This is ultimately still an ideal today.

What are the consequences? The consequences are either to abandon the revolutionary project of freedom and equality – or to adhere more strictly to its main features. Winkler argues that Europe can “do nothing better to spread its values than follow them itself and be self-critical about its own history which broadly speaking was a story of its own ideals being violated” (Winkler, 24) and still is. This also means: ad fontes! What are the origins of this dream, this revolutionary project – and how can we pursue the dream today? And do spiritual communities and movements have a special part to play?

Sr. Nicole Grochowina

by Pal Toth | Apr 4, 2018 | 2018 Europe Day, Experiences, reflections and interviews, News

The following text has been published to facilitate those who for “Together for Europe Day”, to be held on 9th May, are considering leading a Round Table discussion aimed at opening up dialogue in “diversity”. Examples might include dialogues between East and West, North and South, or dialogues between members of different Churches, or between believers and non-believers, indigenous and refugees etc…

Europe’s diversified composition

To frame the European situation well, it is useful to bear in mind its geopolitical and cultural reality.

Western Europe is mainly a socio-political concept and it specifically identifies the European countries of the “first world”, the result of a multi-century political, economic, and cultural path, different from the Eastern European one. Today, the term Western Europe is also commonly associated with liberal democracy, capitalism, and even with the European Union, despite the latter’s inclusion of Eastern European countries. Most of the countries in the Eastern regions share the very Western culture that seems to be undergoing a crisis today. And there are differences and tensions within the West as well, for example between the North and the South. Or, let us think of the Church of England, which after Brexit will surely not want to leave Europe but intensify its relations with it.

Eastern Europe is rather a geographical concept, an area articulated by different traditions and problems within its borders. Culturally, it can be largely distinguished between Central Europe, the Balkans, and the former Soviet Union countries, and religiously speaking, between the Catholic-Protestant and Orthodox spheres, with consequences on thoughts and actions of its peoples. The common denominator are the post-communist conditions characterized by the social and political troubles of a difficult path to democratization. With the extension of the EU to some Eastern countries, new member States are rapidly adapting to the Western economic and legal system, while cultural approaches are much slower.

Building a culture of encounter before anything else

To achieve a fruitful dialogue between East and West, it is necessary to proceed in degrees and not face problems head-on. According to the Together for Europe journey, condensed in 18 years of experience, and densely expressed in the great event in Munich in 2016, it is necessary to shy away from an attitude of criticism and defense, and promote a culture of encounter, mutual acquaintance, and reconciliation.

Over the last few centuries, the East has looked at the West as a cultural and political model and has developed an understanding of what happens in Western countries, while Eastern Europeans often are painfully faced with the Westerners’ lack of knowledge, and the subsequent misunderstandings. Without Westerners acknowledging the values of the East, there can be no equality or reciprocity. So, we need humility, trust, knowledge, and mutual acceptance.

Consequently, I think that, as a first step, we should promote a culture of encounter, create a platform, a “home” where dialogue is possible. At this stage we could also reflect on our cultural traditions and different reasonings, to prepare for constructive dialogue.

Extract from a talk by Pál Tóth “Culture of encounter and the dialogue between Eastern and Western Europe”, Meeting of ‘Friends’ of Together for Europe – Vienna, 10th November 2017

Download the full talk >

by Jesus Moran | Apr 4, 2018 | 2018 Europe Day, Experiences, reflections and interviews, News

Jesús Morán is the Co-President of the Focolare Movement: Degree in Philosophy, Doctorate in Theology. Here are his stimulating thoughts, condensed into 7 points, to learn the “language of fraternity”

1. Dialogue is always a personal meeting. It is not about words or thoughts, but about giving our being. It is not just conversation but something that intimately affects the participants. Rosenzweig used to say: “Something really happens in authentic dialogue”. In other words: you do not leave a true dialogue unscathed, something changes in us.

2. Dialogue requires silence and listening. Silence is fundamental for sincere thinking and speaking. A deep silence, patiently cultivated in solitude and put into practice in front of others, of their way of thinking and speaking. A Hindu proverb says: «When you speak, make sure that your words are better than your silence». Benedict XVI said that today more than ever we need, “an ecosystem that knows how to balance silence, words, images and sounds”. In the exercise of dialogue we need silence, so as not to destroy the words themselves.

3. In dialogue we put ourselves at risk, our vision of things, our identity, our culture. We must conquer an “open identity”, which is mature, and at the same time based on a fundamental anthropological axiom: “When we understand each other, I understand better who I am”. Paraphrasing an idea of Klaus Hemmerle: if you teach me your thinking, I can learn my way of announcing again.

4. Authentic dialogue has to do with the truth. But beware: truth is a relational reality (not relative, which is different). It means that the truth is the same for everyone, but everyone shares his personal participation and understanding of the truth with others. So the difference is a gift, not a threat. “The gift of difference” is another pillar of the culture of dialogue.

5. Dialogue requires will. Love of the truth leads me to look for it, to want it, and for this reason I open myself up to dialogue. Sometimes it is thought that to dialogue is weak. In reality it is the opposite: only those who have great willpower take the risk of dialogue. Every dogmatic or fundamentalist attitude hides fear and fragility. We must be wary of those who habitually resort to screaming, to using high-powered words or disqualifying sentences to impose their convictions. Brute force, even on a dialectical level, can win, but never convince.

6. Dialogue is only possible between authentic people. Love, altruism and solidarity prepare people for dialogue by making them authentic. Gandhi and Tagore had a very different idea of the educational system to be established in an independent India, but this did not hinder their friendship. Pope Wojtyla and President Pertini had, over a long period, a deep understanding of the destiny of humanity, yet they adhered to almost opposite categories.

7. The culture of dialogue knows only one law, that of reciprocity. Only in this does dialogue find meaning and legitimacy. If nations were to engage in dialogue before the silent killing of revenge or wealth or personal affirmation, we would enjoy the happiness of which we now deprive ourselves. If religions were to dialogue to honour God; if nations respected one another and understood that their wealth is in making the other rich; if everyone went through a “little personal path” of novelty, we could leave behind the night of terror in which we reel. What are the obstacles on such a path? Judgment, condemnation, intellectual pride.

The work to be done is painstaking because of the commitment it requires, avoiding distraction or compromise, but it is full of culture, much more than a profession. It is a tiring and ruthless activity. But Mercy will save us.