by TogetherforEurope | Nov 10, 2017 | 2017 Friends | Vienna, Austria, News

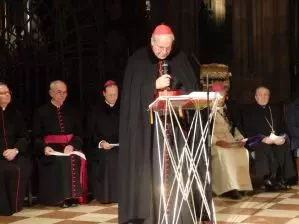

An ardent ecumenical prayer service. On the 9th November, 2017, Vienna Cathedral – dedicated to St Stephen – became the focal point for Europe.

Visible, inviting, and European – this is how this “Ecumenical Evening Prayer for Europe” came across in the cathedral church of Vienna, the Stephansdom.

Members of the ecumenical network Together for Europe at the heart of the Austrian capital city, at the vigil of their annual Congress. They came from countries such as Portugal, Russia, England, and Greece.

Their aim: unity and reconciliation among various Christian denominations and cultures, as well as solidarity and integration within Europe.

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Oekumenisches Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

Cardinal Christoph Schönborn lead an ecumenical group of representatives of various Churches: hundreds of people gathered under the “Lettner” Cross which is a significant memorial of the victims of the two world wars. “People today do not expect us to rule, but to serve,” the Cardinal emphasized in his speech. The solemn prayer for a TOGETHERNESS of cultures and generations and for peace resounded powerfully.

“This moment of prayer was a multilingual, visible, and European sign of hope,” said one of the participants, “and it gives us hope for the future.”

Video Ecumenical Prayer Vienna (German)>

At the reception that followed the celebration, Thomas Hennefeld, Superintendent of the Reformed Church of Austria and President of the Ecumenical Council of Churches in Austria, and Joerg Wojahn, Head of the European Commission Representation in Austria, underlined that Christian values are the basis for a united Europe. “We need everybody,” exclaimed the representative of the EU.

After November 9, 1938 (the Night of Broken Glass) and November 9, 1989 (fall of the Berlin wall), couldn’t November 9, 2017, day of the ecumenical prayer, be a significant step on the road of Together for Europe and a sign for Europe?

Beatriz Lauenroth; Photo: Annemarie Baumgarten

-

-

Empfang nach dem Oekumenischen Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Empfang nach dem Oekumenischen Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Empfang nach dem Oekumenischen Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Empfang nach dem Oekumenischen Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Empfang nach dem Oekumenischen Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Empfang nach dem Oekumenischen Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Empfang nach dem Oekumenischen Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Empfang nach dem Oekumenischen Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

-

-

Empfang nach dem Oekumenischen Gebet Wien 9.11.2017

by TogetherforEurope | Nov 9, 2017 | 2017 Friends | Vienna, Austria, Experiences, reflections and interviews, News

“Hidden treasures” in Vienna

555th anniversary on 31st October 2017! What am I talking about? Let me explain: 500 years since Luther’s Reformation, 50 years since I was born and 5 years since I have moved to Austria.

When I realised this coincidence, I wondered how to celebrate the big round anniversary uniting my personal history with the ecumenical one.

I am a Swiss citizen; my mother is reformed and my father Catholic. My siblings and I were baptised into the Reformed Church, but after we went our separate ways. As a child I joined the Catholic Church, hence my strong passion for the unity of Churches. I now live in a Focolare community in Vienna.

Some time ago, in a meeting of consecrated people in the Ecumenical Centre in Ottmaring, attended by the Lutheran Bishop Emeritus Herwig Sturm, I presented a performance on Luther, based on images, spoken word and dance (I am a ballet dancer by profession). It occurred to me, why not celebrate my birthday by offering the same performance to the public?

-

-

Roswitha M. Oberfeld Foto: privat

-

-

Roswitha M. Oberfeld Foto: privat

-

-

Roswitha M. Oberfeld Foto: privat

On 29th October, more than 60 people gathered in Am Spiegeln, in the Meeting Centre of the Focolare Movement in Vienna, for my ‘ecumenical birthday show’. Instead of bringing birthday gifts, I asked my guests to offer a contribution towards translations of the meeting of Friends of the ecumenical network Together for Europe which was to take place in the Meeting Centre a few days after my birthday.

What a joyful occasion it has been to bring the money raised through the show to the International Steering Committee of Together for Europe!

Roswitha Oberfeld, Vienna (Austria)

by TogetherforEurope | Oct 31, 2017 | Experiences, reflections and interviews, News

A meeting at the Vatican to rethink about Europe. Together for Europe was there.

«In our time, Christians are called to revitalize Europe and to revive its conscience, not by occupying spaces, but by generating processes capable of awakening new energies in society”. Pope Francis said these words at the end of his address to the 350 participants, present at the Vatican for a meeting sponsored by the Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences of the European Community (Comece) in collaboration with the Secretary of State. The title was “(Re) thinking Europe – a Christian contribution to the Future of the European Project” (27 -29 October 2017). This conference was meant to create an opportunity where one could discuss the contribution Christians can give to the European project, with the hope that dialogue put into practice can be of help to Europe and its institutions at this very critical stage.

During meetings held in previous days, Cardinal Marx, Archbishop of Munich and Freising and President of Comece, gave a picture of the continent’s realities, perspectives, challenges and hopes. He spoke of issues, such as environment, work, refugee crisis, that have to be faced “with a very clear vision of our present, and above all of the future”

Msgr Jorge Ortiga, Archbishop of Braga and delegate for the Portugese Bishops’ Conference said, “the European Union needs a soul, it needs something new. This is not the case of just considering the territory or the economy; but it is the responsibility of building one society, one body that expresses diversity, respect for every culture, every country with its different characteristics”

András Fejerdy, professor at the Catholic University of Budapest said: “Even if the Berlin Wall fell 25 years ago, divisions in our minds still exist. Maybe, we who live in the eastern part of Europe know the history, culture and thought of the Westerners better. On the other hand, we face many misunderstandings because of lack of knowledge. I participated in a workshop with representatives from the East and South of Europe, and it was interesting to see that we all share the same hopes and fears about the future of Europe”.

Katrien Verhegge, director general of Kind en Gezin, in Belgium, said: «It is in this context that we promote our message of unity and diversity. For me this means going back to what is essential: love and the golden rule. We can unite ourselves in living the golden rule, “in not doing unto others what we would not have others do unto us”. If we start to live this in our rethinking about Europe, we will already be making a step foward”.

For Pedro Vaz Patto, president of the Portugese Peace and Justice Commission, this is actually a moment “of crisis of confidence in Europe. As Christians, we have tried to contribute towards a Europe in search of a soul. The EU motto is “unity in diversity”. We Christians believe in God, who is one and who is Trinity. So our faith helps to live this unity in diversity, first of all through our witness. Among Christian Movements, Churches, individuals”.

Ilona Toth, Focolare Movement’s delegate for Togther for Europe was among the participants. Together for Europe brings together more than 300 Christian Communities and Movements spread across the Continent. While preserving their independence, these collectively form a network to pursue shared goals, each contributing through its own specific charism. Toth said that: ”The Together for Europe Project is very much in line with what was discussed during this conference and many showed interest in it. We have been invited to Brussels to start work of collaboration, while envisaging the importance of empowering Europe’s peoples to build their history”.

-

-

Ilona Toth representative of TfE

-

-

Rev. Karin Burstrand, Vice-President of the CEC

-

-

left: Rev. Fr Heikki Huttunen, General Secretary of the CEC

-

-

Bishop Heinrich Bedford-Strohm, President of the Evangelical Church in Germany

Significant the presence of leaders of different Churches, including Lutheran Bishop Heinrich Bedford-Strohm, Chair of the Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) and representatives of the Conference of European Churches (CEC): General Secretary Rev. Fr Heikki Huttunen and Vice-President Rev. Karin Burstrand.

At the end of his address, Pope Francis said that the commitment of Christians in Europe “must represent a promise of peace” and that “it is not the time to dig trenches, but to work courageously to realize the founding father’s dream of a united and harmonious Europe, a community of peoples who wish to share a future of development and peace”.

Source: SIF

Address of Pope Francis >

Video: https://vimeo.com/240377109

by TogetherforEurope | Oct 30, 2017 | 2017 Friends | Vienna, Austria, News

From 9th to 11th November 2017, the Friends of Together for Europe will come together in Vienna, a bridge between Easter and Western Europe, for their annual congress.

A total of 120 participants from around 20 Eastern and Western European countries and 40 Movements are expected to attend. Their main aim will be to pool ideas on three topics:

- What culture is generated by the history of Together for Europe?

- What is our specific contribution to Europe?

- Dialogue between East and West: a mutual enrichment

This network of people embraces all of Europe from England to Russia, from Portugal to Greece. Their shared mission: through the upcoming meeting, to strengthen communion among their individual charisms and build united and multifaceted Europe, with strong social cohesion and cultural diversity.

The meeting will open, on 9th November 2017, in the Stephansdom Cathedral of Vienna, with an Ecumenical prayer for Europe. All those who wish for peace in Europe and in the world, are invited to take part in this moment of prayer.

Cardinal Christoph Schoenborn, Archbishop of Vienna, Auxiliary Bishop Emeritus Helmuth Kraetzl, Catholic Church, Archpriest Vicar Ivan Petkin, Bulgarian Orthodox Church in Austria, Chorbishop Emanuel Aydin, Syrian Orthodox Church in Austria, Patriarchal Delegate Tiran Petrosyan, Armenian Apostolic Church, Patrick Curran, Archdeacon of the Eastern Archdeaconry of the Anglican Church in Europe, together with all the present will bring before God needs and opportunities of our continent. The intention of the prayer is extremely timely: unity in diversity, peace in justice.

Following personalities will address the gathering: Thomas Hennefeld, Superintendent of the Reformed Church of Austria and President of the Ecumenical Council of Churches in Austria, and Joerg Wojahn, Head of the European Commission Representation in Austria.

-

-

Invitation TfE Vienna 2017_1

-

-

Invitation TfE Vienna 2017_2

by TogetherforEurope | Oct 26, 2017 | Experiences, reflections and interviews, News

‘Behind the iron curtain’ was a metaphorical attribution given to those countries that from the end of the Second World War until 1989 were part of the communist bloc. The ‘iron’ curtain in question represented the ideological split which divided Europe in two halves, an ideological split physically represented by the Berlin Wall.

When for research purposes I visited Prague, in former Czechoslovakia, the memory of Jan Palach was very much alive with many university students considering him a hero: on 16th January 1969 Jan Palach set himself on fire to draw the attention of the world to the exasperation in which his nation lived. My impression was that in the capital city of Czechoslovakia two parallel worlds coexisted: one official and visible, and another hidden but ever so present.

I had a similar experience living in Hungary in the 1980s. At that time, only a censored and sanitized version of news from Eastern European countries reached the West… Not much was known about Hungary outside the events of 1956. Initially I travelled to Budapest on a research scholarship into children’s literature, but my stay developed into a chain of surprising events and considering the political and historical context – small miracles.

Thanks to the translations I became known for, I received an award which allowed me to remain in Hungary as a lecturer at the Janus Pannonius University of Pecs. In a context of politics manipulated by interests and ideology, the ability to incorporate any kind of positive message into teaching required a sense of personal responsibility and freedom.

On one of my train journeys, while waiting at one of the endless border custom checks, I spotted a bird jumping on the barbed wire fence dividing the two countries. This sight prompted me to ponder how long those barriers would remain and I drew some hope from Giambattista Vico, a philosopher from Naples, Italy, who spoke about the fact that things which are outside their natural order do not remain so.[1]

In 1989, immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall I happened to conduct a sociological study on the change of toponyms of the streets and squares of Budapest and on destiny of statues left in that country by communist realism. These were eventually to be transferred to a specially designated garden which served as a sort of a ‘historical ZOO’ where parents would bring their children on Sundays… Some of the Soviet red star sculptures would have to wait for years to be taken down owing of their sheer size and weight.

After 16 years in Hungary, and after visiting other former Warsaw pact countries such as Slovakia or Poland, and places such as Auschwitz I understood better the reason of my being and I have become more and more grateful to God for the possibility to help make Europe and the entire world a family.

I also feel how right Victor Hugo was in in his famous [mis]quote : “Nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come”.[2]

by Tanino Minuta

[1] Giambattista Vico, Opere Vol. I, Tipografia della Sibilla, Naples, 1834, p. 12. [free translation]

[2] http://nuovoeutile.it/222-frammenti-sulla-creativita-a-cura-di-annamaria-testa/ [http://www.quotecounterquote.com/2011/02/nothing-is-more-powerful-than-idea.html]

by TogetherforEurope | Oct 20, 2017 | News

A dream can become reality

On the eve of the reunion of “Together for Europe” in Vienna (9-11 November 2017), representatives from different Movements present in the Netherlands met in an attempt to answer the question ‘What are the current trends in the Netherlands and in Europe at large that can help inform a model for a united Europe’?

The Netherlands: ready for dialogue

“In the Netherlands, though practicing Christians are a minority, we share a precise task” affirmed Jan Wessels of the protestant network “Missie Nederland”. “Our main concern is to pass on the message of Jesus Christ and in this task, the Movements and the Churches can learn from and support each other “.

“Everyone is looking to make dreams into reality”, observed Ine Sassen-Pouwels (Catholic Charismatic Renewal) – and who better to dream than young people? So why not give young people of different Movements and Churches of the Netherlands “an opportunity to exchange thoughts and questions they have regarding their own life? The experience of the other mature young people might prove instrumental.”

Jeff Fountain, New Zealand born, married to a Dutch citizen, Director of the Schumann Centre for European Studies and expert on Europe posited: “The Netherlands is a cosmopolitan place particularly suited to dialogue about and for Europe” before making reference to King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands, himself of mixed German-Russian origin.

Relationships of life

There was an atmosphere of great mutual respect, and of joy accompanied by a desire to unite forces in order to contribute to European unity, each starting from their own country. “It’s all about relationships”, emphasised Enno Dijkma of the Focolare Movement. “Friendship among us gives wings to our ideas”. Openness to dialogue and the ‘Neighbour Meeting for Europe’ initiative are two promising concepts the Dutch delegation will bring to Vienna on the 9th of November. This meeting will also bring together representatives from Eastern and Western Europe and give them the opportunity to pool their ideas. We await with a great anticipation the positive outcomes of this meeting for Europe.

Beatriz Lauenroth